The first indications of habitation in ancient Arkesini date back to the 3rd BC millennium, highlighting it as one of the Early Cycladic sites of Amorgos and significantly enriching our knowledge of the density of habitation on the island, the criteria for selecting places of permanent settlement, as well as the form of residences of that period.

The place is still used in the Bronze Age, thus being included in the list of Mycenaean sites. Mobile finds further confirm the duration of use of the site in the Protogeometric and Geometric period (11th-8th BC). In particular, we recognize with certainty the residential core of the early historical times of Arkesini in the eastern foothills of the natural acropolis of Kastri. Here, except for some random finds, like two intact vessels with writings kept in the British School of Athens and numerous fragments of written and embossed jars of geometric times, the structures carved in the natural rock are also important: the way of carving and their architectural form differ little from the safest dated relatives in the geometric settlement of Minoa.

Evidence, inscriptions and accidental surface finds, such as shells of written vessels, as well as a fragment of a marble sphinx in the Archaeological Collection of Amorgos confirm the habitation in Archaic times (7th – 6th century BC). In the Classical period (5th-4th century BC) the Cyclades were formed into line with Athens, already from the First Athenian Alliance. Ancient Arkesini still exists, according to the tax lists of Athens, dating to the second half of the 5th century BC, in which the inhabitants of all three towns of the island are referred to by the common name Amorgioi. Inscriptions inform us that the cities of Amorgos, participate also in the Second Athenian Alliance in 357 BC as Amorgioi, while the copper coins bearing the inscription AMO, abbreviated form of the name AMORGIANS, were attributed to the Amorgian Public.

During the Hellenistic period (323-31 BC), after the defeat and total destruction of the Athenian fleet at the naval battle of Amorgos in 322 BC, the control of the Aegean fell to the Macedonians. The city of Arkesini is documented by numerous inscriptions with information about the settlement of people from Naxos in it, from the copper coins of the city, 3rd and 2nd century BC, from other mobile finds, as well as from the impressively preserved building remains, mainly the wall with the bastions and the double gate. The final dissolution of the Macedonian state was achieved by the Romans in 168 BC and in 133 BC. They establish the Province of Asia, to which the three-towns island (tripolis) of Amorgos has since belonged.

Extremely important for our knowledge about the later periods of the ancient city of Arkesini, a fact that also confirms the duration of use of the place, was the finding of a monetary treasure of 60 gold coins (solid) in the acropolis of Kastri. It dates with precision to the years 674-677 / 78, during the reign of Constantine IV (668-687), and is probably related to an official of the Karavisian strategy. Its hiding, in a sea shell, most likely indicates a hostile invasion. According to Marangou, the location of the treasure at the roots of the high, steep and inaccessible rock of Kastriani, reinforces the point of view that then the rock is protected by an artificial fortification, largely built with ancient building material from the adjacent ancient city. The wall of the acropolis is an impressive structure, built with isodomic boulders, excavated from the rock on which it stands. In the upper part of the wall, about 1.20-1.60m thick, openings for shooting are formed. The entrance of the acropolis, in which the Holy Church of Panagia (Virgin Mary) Kastriani is located, stands on the south side. Access is provided by a narrow stone staircase, one step of which bears the inscription “(Apollonos) apotropaio (u)”. The location of the public buildings mentioned in the inscriptions remains unknown, while numerous buildings remains and fragments of monumental statues are precipitated, many of which are later built on the field retaining walls. However, several mobile finds are kept in museums, such as the marble sculptures in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, of Syros, as well as in the Archaeological Collection of Amorgos.

Although the inscriptions and coins depicting figures of gods, such as the helmeted Athena and the ivy crowned Dionysus, provide reliable information about the official cults of the city, at present it is impossible to completely reconstruct the religious life of the Arkesines.

The exact location of the city cemetery is still unknown. Most likely, the archeological remains of two buildings SW and SE of the walled city, on the downhill slope, are roadside burial monuments of the late 4th century BC, as shown by the neatly shaped masonry and the carved rectangular guides. The fragments of marble tombstones, often inscribed, of Hellenistic times are numerous. Our knowledge about the countryside of Arkesini is limited. According to Miliarakis, in the area of Arkesini the most fertile lands of the island are located, the cultivation of which rewarded the Amorgians with rich crops. The event was the target of pirate raids, which justifies the existence of multiple individual forts, the so-called “towers” in the greater Arkesini area, such as the Tower of Agia Triada (Holy Trinity) and the Tower of Giannoulis, which performed multiple functions: surveillance tower, Phryctoria, defensive fort, security storage area of agricultural production, residence of the landowner. In addition, in the wider area, remains of houses and foundations are testified, as well as surface mobile finds, sculptures and inscriptions, elements which indicate dense habitation in antiquity.

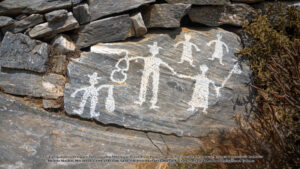

The absence of archeological traces makes it difficult to determine the main road that connected Arkesini with Minoa. Most likely, the transition from Aegiali to Arkesini followed the current course through Balsamitis, and passed through the place where today the Chora is located, a route that is the smoothest option. In fact, in a large part of the road from Valsamitis to Arkesini, Miliarakis evinces iron crosses placed on roadside rocks, several of which were preserved until his time, in 1883, having probably replaced ancient altars, herms and statues of deities on the way. In fact, in the “Sta Grammata” site a rock has engraved letters of archaic type, which mean “Oron”, according to Weil’s publication, specifying, perhaps, the boundaries between Minoa and Arkesini. Inscriptions engraved on a rock, but extremely illegible, have been found on a roadside rock at the entrance of the farmhouses of Agios Ioannis of Vroutsis and near Agios Mamas towards Aegiali. Also, according to the testimonies of Miliarakis, on the road from Valsamitis to Agia Triada three tombs were located, called “Chomata” by the islanders, while many of the chapels, located near ancient monuments, have built-in architectural features and inscriptions of ancient constructions. Carved niches for the installation of offerings by the ancient inhabitants of the island were also found on many roadside rocks, like at the position “ Ston Psilo Tafro”.

Means of access:

CAR

,

BUS

,

TAXI

,

TRADITIONAL PATH: "Itonia" Route

Lefkes (Agia Thekla) – Agioi Saranda – Kamari – Kastri (ancient Arkesini) – Vroutsi – Rachoula – Arkesini (Tower of Agia Triada)

Opening hours:

Open

Entry fees:

Free